PUBLISHED November 2, 2025

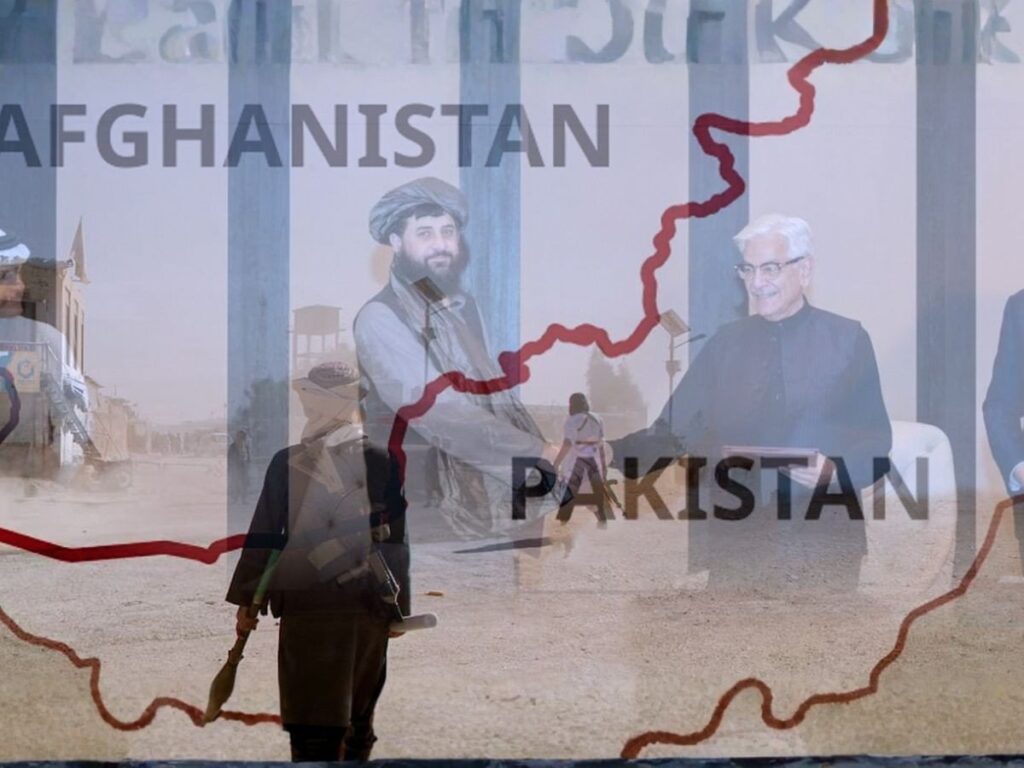

The latest round of talks held in Istanbul, Türkiye from 25 to 30 October 2025 between the Afghan Taliban and Islamabad ended with a tentative agreement to implement the ceasefire previously agreed in Qatar. Further technical aspects of the preliminary understanding will be discussed in the next round of talks starting on November 6, 2025. The international mediation and continued dialogue in the last several weeks is a good omen; But the prospects for a successful dialogue and conflict resolution between Islamabad and the Afghan Taliban remain slim and unpredictable.

This is primarily due to deteriorating bilateral ties between the two neighbors since August 2021. Before Turkey and Qatar, China also made efforts to give peace a chance between the two neighbors in a series of trilateral negotiations, but to no avail. There are four main factors that make peace efforts between the two actors inherently fragile, thereby reducing the likelihood of sustainable peace.

First, Pakistan and the Afghan Taliban lack a common understanding or common position on their main point of contention – the issue of terrorism and the Taliban’s support for Fitna al Khwarj (Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Fitna al Hindustan (Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA).

Since 2021, Islamabad has continued to urge Kabul to take decisive action against the TTP and BLA, citing the groups’ role in exacerbating Pakistan’s security challenges, particularly in the tribal border regions and Balochistan province. Conversely, the Afghan Taliban claim that they do not exercise any form of control over either the TTP or the BLA.

In particular, they have a soft corner for the TTP due to their shared religious ideology and decades of historical experience as insurgent movements. For such groups, the use of force – including acts of violence and terrorism – is often perceived as a legitimate tool to assert their authority over the target group. This fundamental divergence of perspectives on the central issue significantly undermines the prospects for any substantial and lasting conflict resolution between Kabul and Islamabad.

“The Afghan Taliban claim that they do not exercise any form of control over either the TTP or the BLA. In particular, they have a soft spot for the TTP, given their shared religious ideology and decades of historical experience as insurgent movements”.

Second, the dialogue that started in 2025 after a deadly conflict between the two countries should ideally have started in 2021, when the Afghan Taliban took power and the TTP, emboldened by the Taliban’s resurgence in Afghanistan, reactivated its operations and intensified terrorist activities in Pakistan.

Most importantly, both neighbors had to engage each other at various levels and platforms to negotiate various issues of mutual interest such as border security and management, refugee repatriation, counter-terrorism and TTP’s move out of Afghanistan.

The prolonged delay and lack of willingness in such engagement between Kabul and Islamabad has further exacerbated the pre-existing trust deficit – a historical feature of Pakistan-Afghanistan relations largely rooted in the issue of Kabul’s irredentist claims to the Durand Line. Instead of addressing the realities on the ground and sources of trust deficits, both sides resorted to mutual accusations and blame-shifting.

Consequently, these delayed diplomatic efforts, after years of mistrust, will require significant time and commitment to rebuild trust – especially at the grassroots level, where communities on both sides of the border express a genuine desire for conflict resolution and confidence-building measures.

A third major factor shaping Pakistan-Afghanistan relations is the complex geopolitical environment, particularly India’s recent efforts to cultivate friendly ties with the Taliban regime in Kabul. Taliban Foreign Minister Amir Muttaqi’s visit to New Delhi in October 2025 has been seen by many as an Indian effort to diplomatically isolate Pakistan and create a two-front challenge that could strain Islamabad’s strategic position and capabilities.

The wider South Asian region, and Afghanistan in particular, is already facing acute socio-economic difficulties and political uncertainty, and any such geopolitical maneuvering by India and the Afghan Taliban could further destabilize the region, leading to serious implications for development and human security.

It is imperative for India to recognize the fact that provoking the diplomatically and politically inexperienced Taliban will not limit the ensuing conflict and its ramifications to Afghanistan and Pakistan alone; rather, it will create long-term regional consequences that all states in South Asia must bear.

Finally, peacebuilding, negotiations and conflict resolution require that all parties have both the political will and diplomatic capacity to engage constructively. In the case of the Afghan Taliban, they seem to lack both. Their close association with the TTP and other militant and insurgent groups undermines their willingness to confront and resolve the conflict with Pakistan, especially given that the heart of the dispute lies in the Islamic Emirate’s continued logistical and political support for the TTP and the BLA.

In terms of capacity, the Taliban leadership also suffers from limited diplomatic exposure and training. The Taliban Political Office in Qatar had previously shown a degree of political maturity due to its sustained exposure and engagement with the international community that resulted in the 2020 US-Taliban peace agreement.

“Most importantly, both neighbors needed to engage each other at various levels and platforms to negotiate various issues of mutual interest such as border security and management, refugee repatriation, counter-terrorism and TTP’s dislodgement from Afghanistan”.

But as soon as the Taliban congregations returned to power, they sidelined the leadership of the Qatar office, leaving its members with little influence on the Taliban’s important decisions. The prominent role of Mullah Yaqoob – a former Taliban commander and current Taliban defense minister – in the first round of negotiations in Qatar indicated that the Taliban approached this issue from the position of power rather than with the element of diplomatic and political will and maturity – a factor that further diminishes the prospects for a negotiated solution for Pakistan and Afghanistan.

It is imperative to consider these four critical factors when seeking any substantive and sustainable solution to the Kabul-Islamabad conflict. In this context, Türkiye and Qatar, as influential mediators, can play a central role in persuading the Afghan Taliban to recognize the serious humanitarian consequences of a sheltered conflict for the Afghan population, which is already exposed to one of the world’s most serious humanitarian crises, characterized by limited access to climate livelihood opportunities, and unfolding climate livelihood opportunities.

Sadia Sulaiman is Assistant Professor at the Area Study Center for Africa, North and South America, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad.