Conducts court established under 27th amendment; supervised reserved seats and military court sentences.

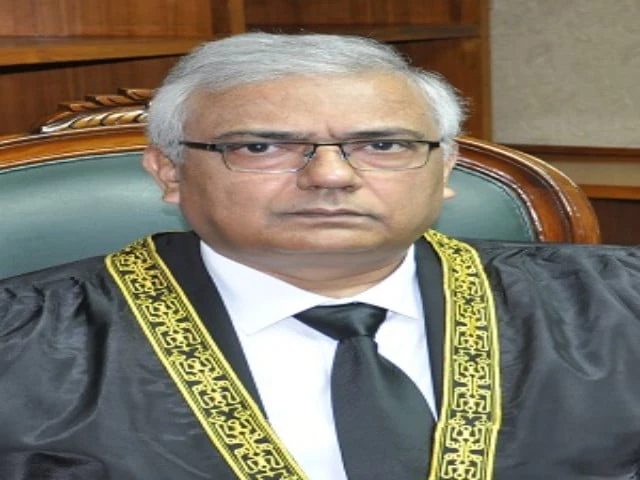

Justice Aminuddin Khan was sworn in as the first Chief Justice of the Federal Constitutional Court on Friday in front of a packed hall of judges, lawyers and dignitaries in Islamabad.

Justice Aminuddin’s appointment follows the passage of the 27th Constitutional Amendment, which is now part of the Constitution following President Asif Ali Zardari’s signature. The change reshapes the judicial structure: the incumbent Chief Justice, Yahya Afridi, will retain the title of ‘Chief Justice of Pakistan’ until they complete their tenure, while the senior between the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and the Chief Justice of the Federal Constitutional Court will be recognized as Chief Justice of Pakistan Afri Yairhyesa later after Justice Yairhyesa Pakistan. It also authorizes the president to appoint FCC judges on the advice of the prime minister — a move that has sparked intense debate in legal circles.

Read: The President signs the 27th Amendment into law

The Federal Constitutional Court represents a long-standing democratic commitment first envisioned in the 2006 Charter on Democracy signed by the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N). Justice Aminuddin Khan’s nomination is perfectly in line with the CoD’s original intent. It is to create a specialized constitutional body to strengthen judicial independence and allow the Supreme Court to focus on appellate work.

As Chief Justice of the FCC, Justice Aminuddin will oversee a bench of seven judges — four from the Supreme Court and two from the High Courts — with a retirement age of 68, three years beyond the Supreme Court’s age. The court has exclusive jurisdiction over constitutional interpretation, intergovernmental disputes and presidential or parliamentary references, marking a structural transformation in Pakistan’s judicial landscape, one that Justice Aminuddin is uniquely positioned to lead.

Still, his nomination has sparked consternation in legal circles. Critics note that Justice Aminuddin authored the ‘reserved seats ruling’ that enabled the government’s two-thirds majority, approved the ‘trial of civilians in military courts’ and consistently sided with the executive on judicial appointments at JCP meetings. For them, elevating the same judge to head the country’s new highest constitutional court signals a consolidation of power at a time when judicial independence is already under pressure.

The judge, whose ruling in the reserved seats case helped the government get a 2/3 majority in the National Assembly, allowed civilian prosecutions in military courts and upheld almost all executive decisions related to judicial appointments during JCP sessions, is being nominated as the chief justice of the…

— Hasnaat Malik (@HasnaatMalik) 13 November 2025

Justice Aminuddin Khan’s elevation follows a long judicial career spanning four decades. Born in Multan in 1960 to a family of lawyers, he began practicing law in 1984 under his father, Khan Sadiq Muhammad Ahsan. He was enrolled as an advocate of the Lahore High Court in 1987 and became an advocate of the Supreme Court in 2001. He was appointed to the Lahore High Court in 2011 and elevated to the Supreme Court in 2019, where he currently heads the Constitutional Bench.

Along with the Chief Justice and Justice Mansoor Ali Shah, he joined a three-judge panel under the Supreme Court (Practice and Procedure) Act, 2023, which was tasked with deciding which constitutional cases would be referred to the new court. His inclusion underscored his growing institutional authority and trust among other judges.

In November 2024, following the passage of the 26th Constitutional Amendment, the Judicial Commission of Pakistan (JCP) voted to appoint him as the head of the newly constituted seven-judge Constitutional Court of the Supreme Court. The decision, passed by a narrow majority of seven to five, placed Justice Aminuddin at the head of a bench with exclusive jurisdiction over constitutional interpretation, marking a major shift in Pakistan’s judicial power dynamics.

Among his notable contributions is his dissenting opinion in the reserved seats case on 12 July. He was also a member of the nine-judge panel that examined the President’s reference regarding the hanging of former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Throughout his career, Judge Aminuddin has authored numerous decisions in civil and constitutional law. As head of the Constitutional Bench, he has overseen cases related to constitutional interpretation and judicial review, contributing to the legal framework underpinning the FCC. The FCC, created under the 27th Amendment to the Constitution, has exclusive authority over constitutional interpretation, federal-provincial disputes, and matters referred by the President or Parliament. Justice Aminuddin has been appointed as its first Chief Justice shortly before his Supreme Court retirement, leading the court from its inception.

reserved seats

The reserved seats case concerned the allocation of parliamentary seats to women and minorities after the February 2024 general elections. The main issue was whether PTI candidates who contested as independents after losing their party symbol and joining the Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC) were eligible. The case had significant political implications, potentially affecting the ruling coalition’s majority in the National Assembly.

Read more: ‘PTI was not a party in reserved seats case’: SC judges dissent

The first 13-member Supreme Court bench, headed by then CJP Qazi Faez Isa, ruled PTI eligible for the reserved seats, overturning earlier Election Commission and Peshawar High Court decisions. Justice Aminuddin, with Justice Naeem Akhtar Afghan, dissented, noting that PTI was not a party to the suit and that the grant would exceed the court’s constitutional jurisdiction. He argued that the PTI was not a party to the ECP or the High Court, stressing that decisions inconsistent with the Constitution cannot bind constitutional institutions and PTI’s claim through the SIC was procedurally invalid.

In June 2025, the constitutional bench headed by Justice Aminuddin reviewed the case. On 29 June 2025, it set aside the 12 July 2024 decision declaring PTI ineligible for reserved seats and restored the Peshawar High Court’s original decision, which had rejected PTI’s claim as the SIC had not participated in the election. Seven judges fully supported review petitions filed by the Election Commission, PML-N and others, while three partially allowed them. Dissenting opinions of Justices Ayesha Malik and Aqeel Ahmed Abbasi were considered. The judgment clarified that PTI candidates who had joined the SIC could face disqualification under Article 63A if they rejoined the PTI. Reserved seats under Articles 51 and 106 and the Electoral Act were confirmed to go to coalition parties.

The verdict was a major setback for the PTI, confirming its ineligibility for reserved seats in national and provincial assemblies. It strengthened the role of the Election Commission and compliance with the constitutional procedure. Justice Aminuddin’s dissent in the original ruling highlighted his focus on constitutional compliance and procedural correctness.

Military courts

The case examined the constitutionality of prosecuting civilians under military courts, including the 9 May 2023 riots and the 2009 GHQ attack. Petitioners argued that such trials violated constitutional guarantees, including Article 10A of due process, and challenged previous Supreme Court judgments.

A constitutional bench headed by Justice Aminuddin, by a 5-2 majority on 23 September 2025, held civilian trials under the Army Act ‘constitutional’ if conducted within statutory limits and procedural safeguards. Justice Aminuddin wrote that military courts provide the right to counsel, cross-examination and appellate review under Section 133-B, stressing that justice does not require military courts to mirror civilian courts.

The judgment clarified that military trials adhere to minimum standards of fairness and due process when statutory procedures are followed. Military courts do not replace civilian courts, but operate in a defined legal space related to national defense and operational needs. Noting the absence of independent appellate review in civil courts as a procedural loophole, the bench called on Parliament to legislate for appeals to the High Court. Previous decisions cracking down on such lawsuits were rejected, and the court emphasized constitutional restraint.

Read also: Army says ‘no compromise’ with May 9 planners, executors

Justices Jamal Khan Mandokhail and Naeem Akhtar Afghan dissented, arguing that civilian trials in military courts violate fair trial standards and the principle of separation of powers.

During the case, the court reviewed historical cases, including the 2009 GHQ attack, and noted that military courts are specialized statutory forums, not part of the general judiciary. The judgment also addressed concerns about impartiality and the scope of military jurisdiction, clarifying that military courts operate under statutory authority within operational requirements.

The judgment confirmed the legality of civilian trials under the Army Act, while recommending legislative reforms to provide independent appeal rights in the High Courts. Justice Aminuddin’s judgment defined the scope of military jurisdiction over civilians and established procedural safeguards that balanced operational requirements with constitutional principles.