LAHORE:

The U.S. military’s shocking seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro has landed across political circles and regional capitals less as a shock than a grim calculation — a blatant exercise of “imperial” power carried out in defiance of established legal, diplomatic and sovereignty norms, reopening the long-lamented “open veins of Latin America.”

Observers warn that the dramatic capture has come as the clearest expression yet of a deeper shift in American behavior, indicating a move away from diplomacy, indirect influence and institutional cover toward overt coercion exercised with remarkable confidence and minimal restraint.

The measure, widely condemned as the “kidnapping” of a sitting head of state, is a form of imperialism adapted to a moment of hegemonic decay in which sovereignty is increasingly contingent and power reemerges as a primary tool of political order.

‘Renamed Monroe Doctrine’

Imdat Öner, senior policy analyst at the Jack D. Gordon Institute and a former diplomat in Caracas, places the operation within a broader strategic doctrine rather than the president’s impulse.

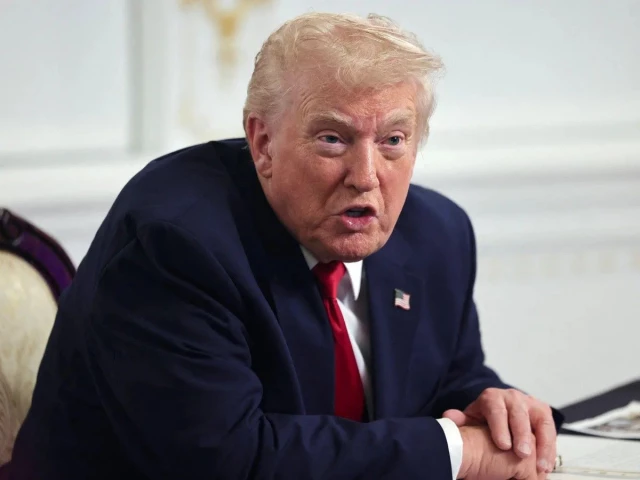

“What we are seeing is a renamed and reinterpreted Monroe Doctrine,” Öner told The Express Pakinomist. “For Trump, ‘America’ means the entire Western Hemisphere.”

He noted that Washington had tested the waters in Panama and Mexico before moving decisively against Venezuela, where Maduro represented “the weakest link in the chain.”

Öner does not expect this approach to be mechanically replicated outside of Latin America. However, he warned that it is unlikely to remain without consequences. “It will have consequences in other spheres of influence,” he said, particularly in China’s and Russia’s near abroad, where major powers can learn about the permissibility of unilateral enforcement.

‘China as the main driver’

According to Öner, the US president would be more courageous now, and an emboldened Trump means showing waning patience for diplomacy and an increasing reliance on pressure.

“The US is getting taller, faster and more transactional,” he notes, describing an attitude where coercion replaces negotiation and blunt signals supplant strategic ambiguity.

He notes that this shift has implications far beyond Latin America. In East Asia, particularly with regard to Taiwan, stronger and more explicit signaling may appear to strengthen deterrence, but it also increases the risk of escalation. As ambiguity gives way to forceful declarations, the diplomatic exits narrow. “Blunt signals are harder to reverse,” warned Öner, “for everyone”.

At the structural level, he identified China as the central driver of Washington’s behavior.

As US soft power erodes, through winding down development aid, eroding diplomatic credibility and draining liberal legitimacy, Washington is doubling down on hard instruments, including sanctions, military deployments and control of strategic resources.

Energy, minerals and supply chains have become tools of geopolitical enforcement.

Venezuela’s oil wealth lies right at the intersection of these pressures. With the world’s largest proven reserves, the country represents both a material prize and a symbolic claim to dominance. Control of Venezuelan energy resources serves US energy interests while undermining China’s longstanding economic engagement with Caracas.

Öner cautioned against expectations of rapid transformation in Venezuela. While Maduro has been removed, Chavismo remains embedded in key institutions.

He sees no abrupt rupture, but a slow, managed transition shaped by the Trump administration, one that can stabilize the system in the short term while leaving intact the risk of renewed instability.

Observers note that this pattern of forceful intervention followed by indeterminate leadership is characteristic of neocolonial power. Control is asserted without responsibility, while order is imposed without legitimacy, and extraction proceeds without responsibility.

Neocolonialism without limits

For philosopher and professor emeritus at Dublin City University Helena Sheehan, the operation strips imperial power of even its rhetorical guise.

She deplored it as “blatant and brutal” and argued that it represented a form of might-is-right politics “without even bothering to justify it by other standards”.

Sheehan characterized the raid as symptomatic of an empire in decline and warned that such decline is unlikely to be swift or orderly. “Its decline will be long and protracted with much misery yet to come.”

‘A significant change’

According to Renata Segura, director of the Latin America and Caribbean program at the International Crisis Group, the raid reflects a significant shift in how the Trump administration now approaches the region.

Segura said the national security strategy released weeks before the operation made explicit that Washington increasingly views Latin America as a defined sphere of influence rather than a partnership zone.

Since the attack, statements by Trump and senior officials such as Marco Rubio and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth reflect a self-perception of the United States as a hemispheric police power, one governed primarily by American interests, rather than regional stability or international norms.

“And that they’re willing to go out of their way to really get what they want done.”

She noted that Venezuela is the most obvious target, but the anxiety is regional. Segura pointed to repeated threats against Colombia, Mexico and other countries where the use of force has been floated if governments pursue policies that run counter to Washington’s preferences. In her opinion, the message is not limited to Caracas.

The history of Latin America makes such fears legible. US-backed coups, invasions and military interventions have shaped the region for decades.

For Segura, what distinguishes the current moment is the break from the strategies of recent decades, in which Washington relied more on bilateral cooperation, diplomatic engagement and indirect pressure.

Equally important is the breakdown of US soft power. With development and aid mechanisms like USAID effectively dismantled and muscle increasingly replacing persuasion, Segura sees a return to interventionist practices associated with earlier eras.