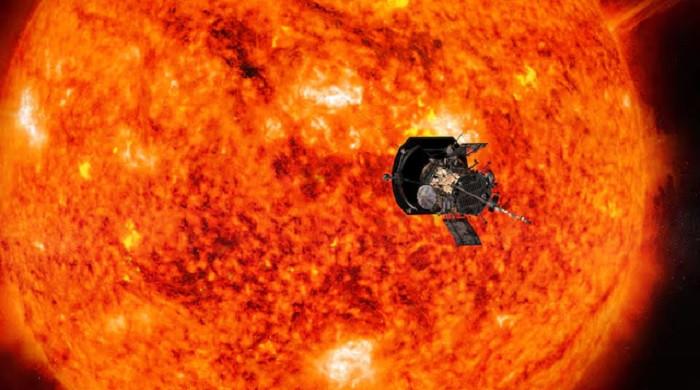

Outbreaks of plasma jumping on each other, solar winds that stream out in exquisite details-the nearest images ever of our sun is a gold mine for scientists.

Caught by the Parker Solar probe under its closest approach to our star, which started on December 24, 2024, the images were recently released by NASA and is expected to elaborate on our understanding of space weather and help protect against solar threats from the Earth.

A historical achievement

“We’ve been waiting for this moment since the late fifties,” Nour Rawafi, project scientist for the mission at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory told AFP.

Former spacecraft has studied the sun, but far further away.

Parker was launched in 2018 and is named after the deceased physicist Eugene Parker, who in 1958 theorized the existence of the solar wind – a constant stream of electrically charged particles blowing out through the solar system.

The probe recently entered its last lane, where its closest approach takes it to only 3.8 million miles from the Sun’s surface — a milestone first achieved on Christmas Eve 2024 and repeated twice ago on an 88-day cycle.

To put the proximity into perspective: If the distance between the earth and the sun was measured in one foot, parks would hover only half an inch away.

Its heat shield was designed to withstand up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,370 degrees Celsius) – but to the team’s joy it has only experienced about 2,000 ° F (1090c) so far, revealing the boundaries of theoretical modeling.

Remarkably, the probe’s instruments remain, just a yard (meters) behind the shield, at a little more than room temperature.

Stare at the sun

The spacecraft carries a single image image, Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe (WISPR), which caught data as Parker threw himself through the sun’s corona or the outer atmosphere.

The new images stitched in a second-long video reveal coronal mass drafts (CMEs) massive cages of charged particles that drive space weather-in high resolution for the first time.

“We had several CMEs stacked up on top of each other, which is what makes them so special,” Rawafi said. “It’s really amazing to see that dynamics are happening there.”

Such outbursts triggered the widespread Auroras seen across large parts of the world last May as the sun reached the peak of his 11-year cycle.

Another striking feature is how solar winds flowing from the left of the image track a structure called the Heliospheric Power Sheet: an invisible border where the sun’s magnetic field flips north to south.

It extends through the solar system in the form of a twisted skirt and is critical of studying as it controls how solar eruptions are propagated and how strongly they can affect the soil.

Why it matters

Space weather can have serious consequences, such as overwhelming power grids, disrupting communication and threatening satellites.

As thousands of more satellites enter into circuits in the coming years, it will become increasingly difficult to trace them and avoid collisions – especially during sun disorders, which can cause the spacecraft to drive a little from their intended circuits.

Rawafi is particularly excited about what lies in front of us as the sun goes towards the minimum of its cycle expected in five to six years.

Historically, some of the most extreme space weather events have taken place in this falling phase – including the notorious Halloween – Solstorms in 2003, which forced astronauts aboard the International Space Station to protect themselves in a more shielded area.

“Catching some of these big, huge outbursts … would be a dream,” he said.

Parker still has far more fuel than engineers originally expected and could continue to operate for decades – until its solar panels are broken down to the point where they can no longer generate enough power to keep the spacecraft properly oriented.

When its mission finally ends, the probe will slowly break down – and stay with Rawafi’s words “part of the solar wind itself.”