Mathare, one of the country’s largest slums, houses up to 500,000 people on five square kilometers who cling them together and store the human waste they produce in uncovered rivulets. But when he told the visit later to the UN news, this was not the picture that was most firm with him.

Without formal sewer systems, rivulets in the mathare slum in Nairobi keep human waste.

What he most clearly remembered was a group of boys and girls, dressed in navy blue school uniforms – the girls in skirts and the boys in pants, both with miniature bands under their vests – surrounded by itchy chickens and human waste.

There was no formula or unicef-funded school nearby. But the Mathare Society was gathered to create a school where their children may just have the chance to break an intergeneration cycle of poverty and invisibility.

“It was a message for me that the development should be located. Something is happening in society [level]”Said Mr. Jobin.

Globally, over a billion people live in crowded slums or informal settlements with inadequate housing, making this one of the biggest development problems worldwide, but also one of the most underrecognized.

“The first place where the opportunity begins or is denied is not an office building or a school. It is in our home,” UN Deputy Secretary General Amina Mohammed told a high -level meeting in the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) Tuesday.

A lacquer test

Mr. Jobin was one of the experts who participated in the high-level political forum (HLPF) on Sustainable Development at the UN Headquarters in New York this month to discuss progress-or is missing from the globally agreed 17 Sustainable Development Objectives (SDGs).

One of the goals strives to create sustainable cities and communities. But with almost three billion people facing an affordable housing crisis, this target remains unrealized.

“Housing has become a lacquer test of our social contract and a powerful goal of whether development really reaches people or quietly bypass them,” said Rola Dashti, Under Secretary General of the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (Escwa).

Housing as mirror for inequalities

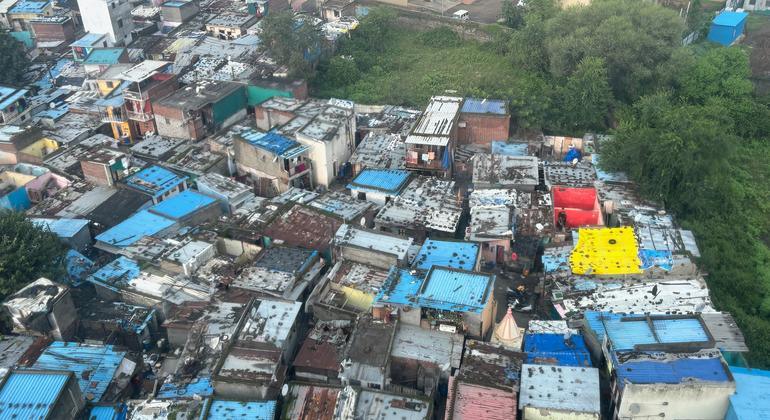

An apartment building at an informal settlement in Mumbai, India.

With over 300 million unhoused people all over the world, it is sometimes easy to forget the one billion people who are housed but inadequate. These people who populate informal settlements and slums live in unstable housing and in communities where few services are provided.

“Housing reflects the inequalities of shaping people’s daily lives. It signalizes who has access to stability, security and opportunity, and who doesn’t,” said Ms. Dashti.

Children living in slums or informal settlements are up to three times more likely to die before their fifth birthday. They are also 45 percent more stunted than their comrades as a result of poor nutrition.

Women and girls are more likely to experience gender -based violence. And human trafficking and exploiting children are also more widespread.

An intergenerational invisibility

People in informal settlements are often not part of the national census, according to Mr. Jobin, which means they are not taken into account in policies, social programs or budgets. Even if they were given social protection, these settlements rarely have addresses where families could receive cash transfers.

This is why experts often say that the people living in informal settlements and slums are invisible in official data and programs.

“You are born of an invisible family so you become invisible,” said Mr. Jobin. “You do not exist. You are not reflected in policies or budgeting.”

This invisibility makes it almost impossible to escape poverty.

“You get a prisoner of a vicious circle that entertains itself, and then you reproduce yourself to your child,” he said, referring to an inevitable deprivation cycle.

The urban paradox

More and more people are migrating into urban centers, leading to the growth of these informal settlements. And with their growth, more urgent comes to tackle the problems.

The World Bank estimates that 1.2 million people move to cities every week and often seek the opportunities and resources they offer. But millions of people are never able to benefit, rather than being forgotten in an urban paradox depicting urban wealth as a protection against poverty.

By 2050, the number of people living in informal settlements is expected to triple to three billion, one -third of which will be children. Over 90 percent of this growth will occur in Asia and Africa.

“These statistics are not only numbers-they represent families, they represent workers and whole communities that are left behind,” said Anacláudia Rossbach, Secretary General of UN Living Venues working to make cities more sustainable.

The Mathare slum in Nairobi houses 500,000 people within 5 square kilometers.

Housing as human rights

It is not only national and local authorities who are struggling to fight with informal settlements – organizations like UNICEF are also “blind,” said Mr. Jobin on the extent of problems in informal settlements.

Development partners face two questions in the design of interventions – there are not enough national data and informal governance or slum gentlemen may be more critical for coordinating programs than traditional state partners.

“We know the problem … but somehow we haven’t really been able to intervene,” he said.

Ms. Mohammed emphasized that we have to start to see sufficient and affordable housing as more than just a result of development – this is the foundation on which all other development must rest.

“House is not just about a roof over one’s head. It is a basic human right and the foundation on which peace and stability itself rests.”