My latest NoteBooklm -Podcast creation is deeper and more fascinating than anything else I’ve ever created and I bet it will shock you too.

I don’t understand string theory. In fact, I know that there are fewer than 1% of the world that can talk cogent on the subject, but I am fascinated by the concept and have read a little about it. Not enough to understand or explain it to you, but enough to have a steady and persistent curiosity.

AI, on the other hand, I think I understand and now regularly use as a tool. As Google released a recent NoteBooklm update, which includes, among other things, Mind Maps, I thought it was time to gather something from the very external edges of my understanding and this bleeding-edge-artic intelligence capacity.

So I created a String Theory -Podcast.

First a small primer on the notebooklm. It is a powerful AI-based research tool where you can upload sources, and it will make them summary and extrapolated information in the form of text, podcasts and visual guides as a thought card.

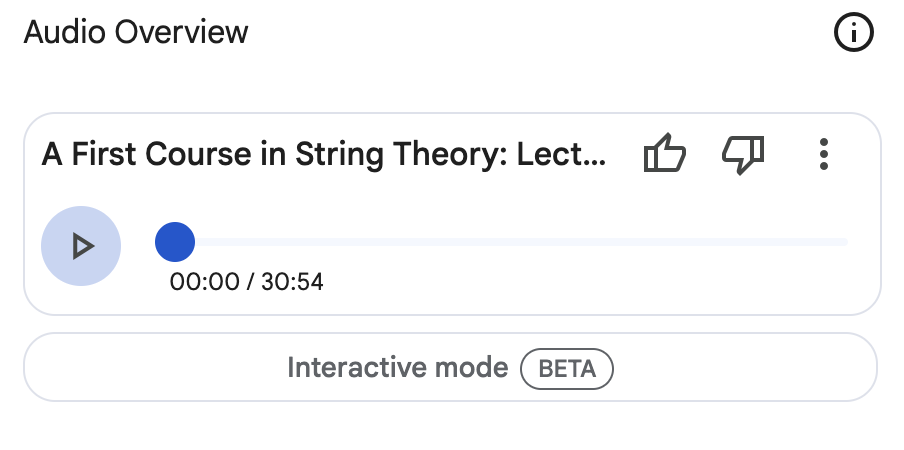

For me, the most fascinating bit has been podcasts or “audio overviews” that throw Chattty audio conversations on almost any topic you feed into them. I call it a podcast because the sound style goes a well worn path with the most popular podcast series. It’s conversation, usually between two people, sometimes fun and always available.

However, I have speculated if you can stretch the boundaries of the format with a topic that is so deep and honest, confusing that the resulting podcast would be conversation -wrap.

My experiment, however, proved that although the current version of Notebooklm has its boundaries, it is far better at understanding close scientific bits than me and probably most people you or I know.

Strange science

When I decided I would have notebooklm to help me with the subject, I went in search of string theory content (there is much more of it online than you might think), quickly stumbled over this 218-page research document from 2009 by the University of Cambridge researcher Dr. David Tong.

I scanned the doctor and could tell that it was rich in string theory details, and so far over my head it is probably somewhere near Saturn’s rings.

Imagine trying to read this document and make sense of it. Maybe if someone Explained That to me I would understand. Perhaps.

I downloaded PDF and then fed it to notebooklm where I requested a podcast and a thought card.

It took almost 30 minutes for notebooklm to create the podcast and I have to admit, I was a little anxious when I opened it. What if this detailed mass on one of the most confusing topics of physics overwhelmed Google’s AI? Can the hosts just bable incoherent?

I shouldn’t have worried myself.

I had heard these podcast hosts before: a somewhat vanilla couple (a man and a woman) randomly quarreling while making witty sides. In this case, they tried to explain string theory to the uninitiated.

They started by talking about how they would go through the subject, cover bits such as general relativity, quantum mechanics, and how at least from 2009 we had never observed these “strings”. Earlier this month, some physicists claimed that they had actually found the “first observation certificate that supports string theory.” But I’ll take off.

The hosts spoke as physics experts, but where possible, in Layman’s terms. I quickly found that I wanted them to have a guest. The podcast would have worked better if they were clerk to me, not at all understood much and had an AI-generated expert to interview.

String it all together

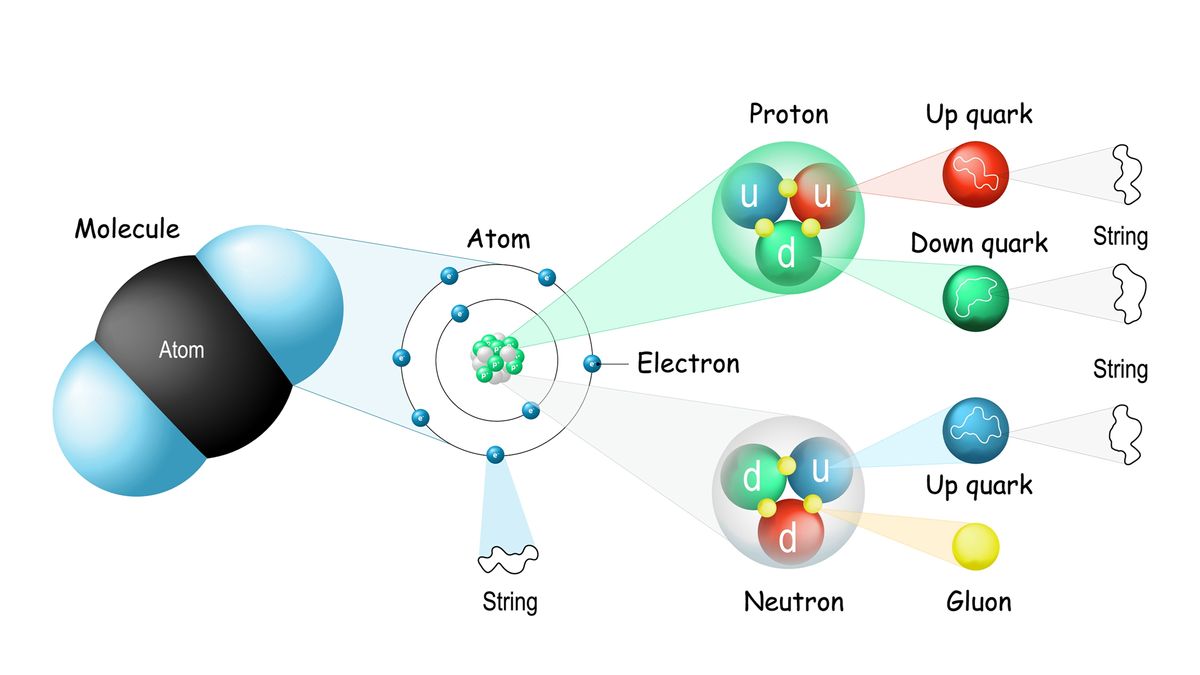

As the podcast progressed, the hosts dug in the details of the string theory, specifically the definition of a “string.” They described them as small objects that vibrate and add, “all things in the universe come from how small strings vibrate.”

Things became more complex from there, and while the AI podcast hosts never changed, I struggled to follow. I still can’t tell you what “relativistic point particle seen through Einstein’s special relativity” really means. Although I appreciated the analogy with “Imagine a string that moves through space time.”

The AI hosts used different tricks to keep me engaged and not completely confused. The male host, like a podcast parrot, would often repeat a little of what the female host had just explained, and use some decent analogies to try to make it relatable.

At times, the female host lapsed in what sounded like she was reading straight out of the research document, but the male host was always there to pull her back to entertainment mode. He made a lot of talking summary.

I felt that I was coming again when they explained how “String transformed into the theory of everything” and added, “Bosons and fermions, partners of crime because of supersymmetry.”

This was heavy

After 25 minutes of this, my head was filled to the point where they jumped were blown up with the still theoretical strings and spinning with expressions such as “Spread Point Operators” and “Holomorphic.”

I was hoping for a magnificent and wonderful summary at the end, but the podcast suddenly ended almost 31 minutes. It was cut off as if the hosts ran out of power, ideas or information and went away from the microphones in frustration and without logging off.

In some ways it feels like this is my fault. After all, I forced these Sims to learn all these things and then explain it to me because I could never do it. Maybe they got tired.

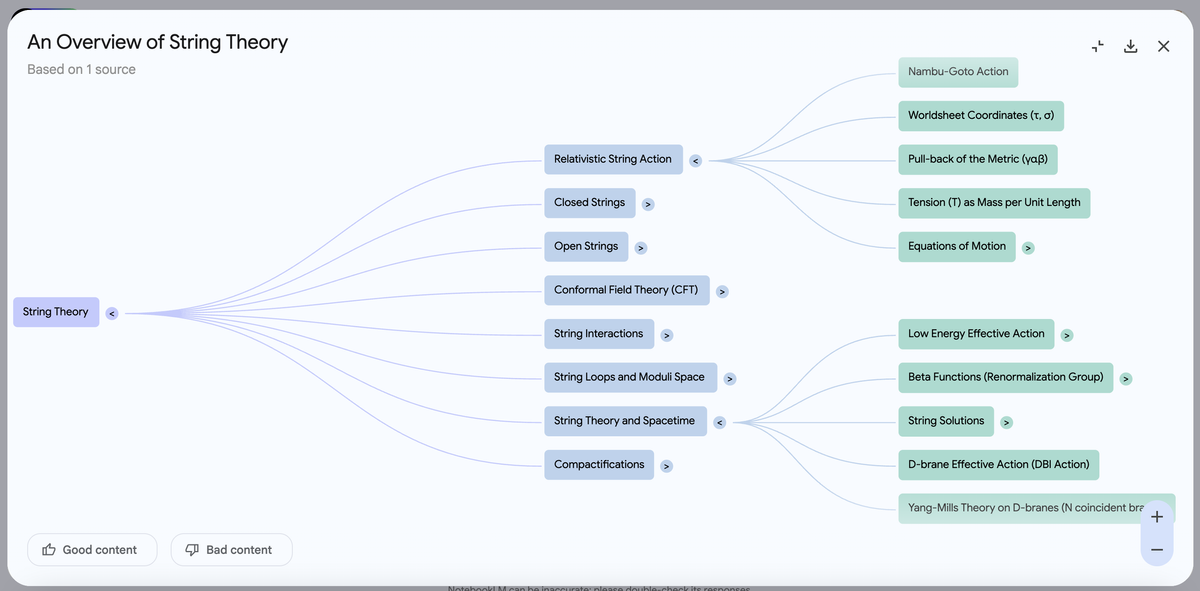

I also checked Mind Maps, which are branching charts that can help you map and represent complex topics such as string theory. As you can imagine, the mind starts short for this topic simple, but becomes increasingly complicated as you expand each branch. They are still a lovely study buddy for the podcast.

It is also worth noting that I could enrich the podcast and mind cards with other research sources. I simply want to add them to the source panel in the notebooklm and run the “audio overview”.

A real expert weighs in

For as much as I learned and as much as I trust the source material, I speculated on the accuracy of the podcast. AI, even with solid information, can hallucinate or at least mistakenly interpret. I tried to contact the paper author, Dr. Tong, but never heard back. So I turned to another physics expert, Michael Lubell, professor of physics at City College of Cuny.

Dr. Lubell agreed to listen to the podcast and give me some feedback. A week later he emailed me this short note, “Listened straight to the String Theory -Podcast. Interestingly presented, but it requires a reasonable amount of expertise to follow it.”

When I asked about any obvious mistakes, Lubell wrote: “Nothing obviously, but I never did string theory research.” Fair enough, but I’m willing to bet Lubell understands and know more about string theory than I do.

Maybe the AI podcasts now know more about the subject than any of us.