“We’re in AI time,” that’s what I’m telling people now as they try to understand the rapid pace of AI and all connected technologies, progress.

Although only two and a half years ago Openai Unleashed Chatgpt on the world, I have known intuitively for months that in the world of technology we no longer operate on Moore’s law: The number of transistors on a chip doubles every two years. This is now AI model law, where generative model functions are doubled every three months.

Even if you do not think that large language models (LLMs) are evolving at that pace, there is no one to deny the unprecedented adoption speed.

A new report (or rather a 340-page presentation) from Mary Meeker, a general partner at Bond Investments, paints the clearest image yet of AI’s transformative character and how it is unlike any other previous tech epoke.

“The pace and extent of change related to artificial intelligence technology development is actually unprecedented, as supported by the data,” wrote Meeker and her co-authors.

Google, what?

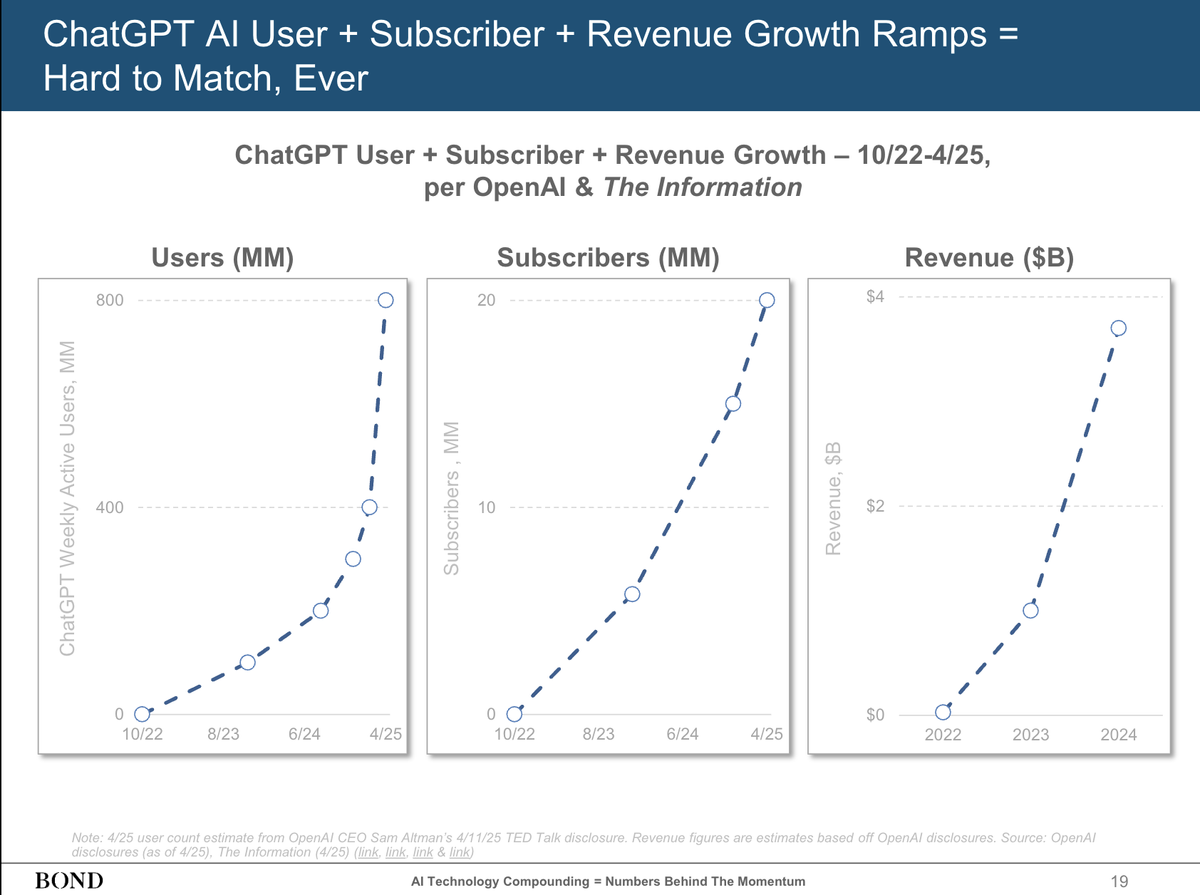

Especially a state stood out for me: It took Google nine years to reach 365 billion annual searches. Chatgpt reached the same milestone in two years.

Meeker’s presentation illustrates something I have been trying to formulate for some time. There has never been a time quite like this.

I have lived through some major technological changes: the increase in personal computing, changed from analog to digital publishing tools and the online revolution. Most of this change, however, was gradually awarded, it felt quickly at the time.

I first saw digital release tools in the mid -1970s, and it wasn’t until the mid -1980s that many of us changed, which is also about the time personal computers began to arrive, though they would not become ubiquitous for at least another decade.

AI time leaves some time, I think, to self-reflection.

When the public internet arrived in 1993, it would be years before most people were on broadband. Knowledge workers did not get up immediately. Instead, there was a slow and stable shift in the workforce.

I would say that we had a decade of solid adjustment before the Internet, and its associated systems and platforms became an inexpensive part of our lives.

I still remember how confused the average person was of the internet. At Today Show in 1994, the hosts literally asked: “What is the internet?” AI and platforms such as Chatgpt, Copilot, Claude AI and others have not met the same level of confusion.

Sign up

Meeker’s report notes that chatgpt -users skyrocket from zero in October 2020 to 400 mi end of 2024 and 800m in 2025. A shocking 20 m people pay subscribers. It took decades to convince people to pay for any content on the Internet, but for AI, people are already on their way up with their wallets open.

I suspect that the increase on the Internet and ubiquitous and mobile computing may have prepared us for the AI era. It is not as if artificial intelligence appeared from the blue. Then it did kind of.

Almost a decade ago, we wondered about IBM’s deep blue, the first AI to beat a chessbed champion Gary Kasparov. It was followed in 2005 by an autonomous car that completed the Darpa challenge. A decade after that, we saw Deepmind AlphaGo beat the world’s best Go player.

Some of these developments were surprising, but they arrived at a relatively digestible pace. Still, things started picking up in 2016, and different groups began to sound the warning bells about AI. No one used public terms “llm” or “generative”. Still, the concern was that IBM, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft and Google Deepmind formed the nonprofit partnership of AI, which was intended to “address opportunities and challenges with AI technologies for the benefit of people and communities.”

This group still exists, but I’m not sure anyone is aware of its recommendations. AI time leaves some time, I think, to self-reflection.

A 2016 Stanford University Survey of AI by 2030 (no longer available online) noted that “Unlike the more amazing predictions for AI in the popular press, the study panel found no need to worry that AI is an impending threat to humanity.”

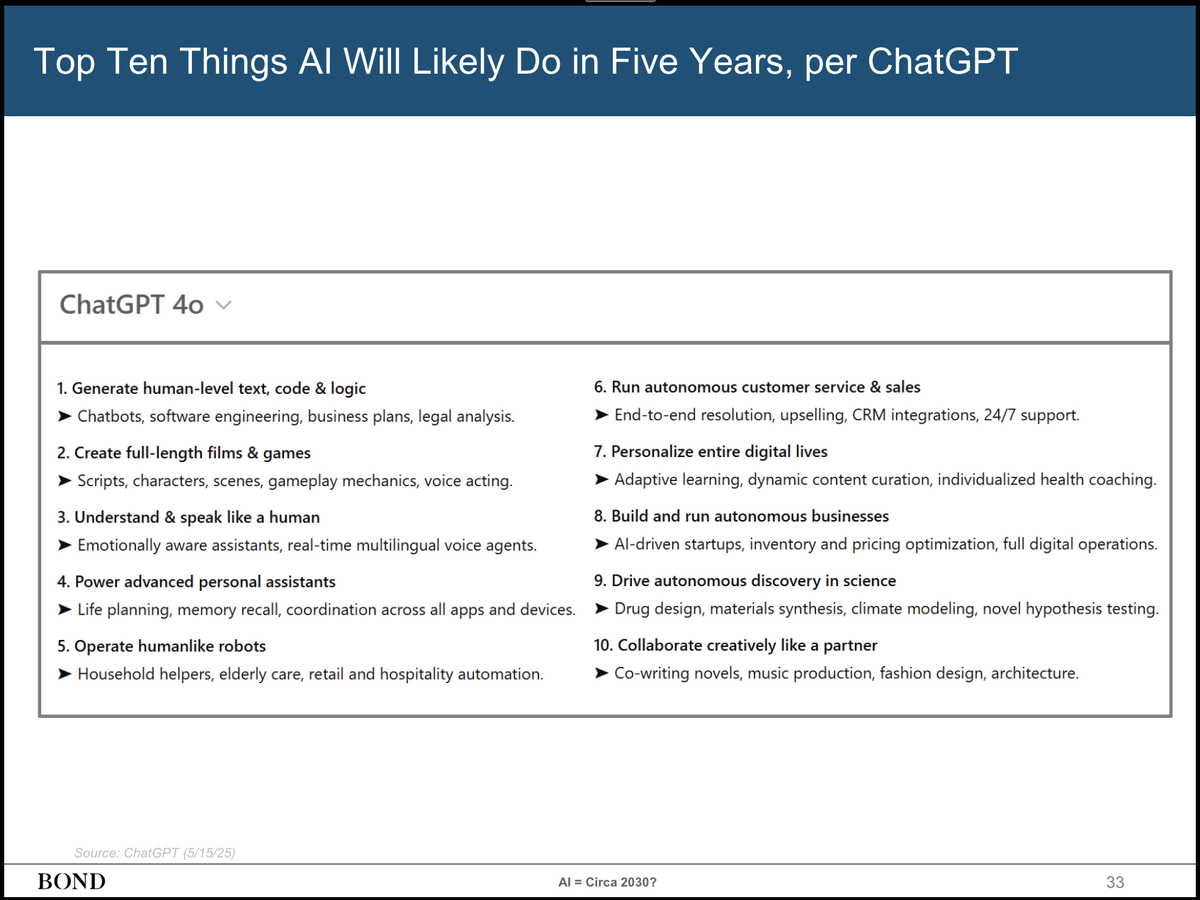

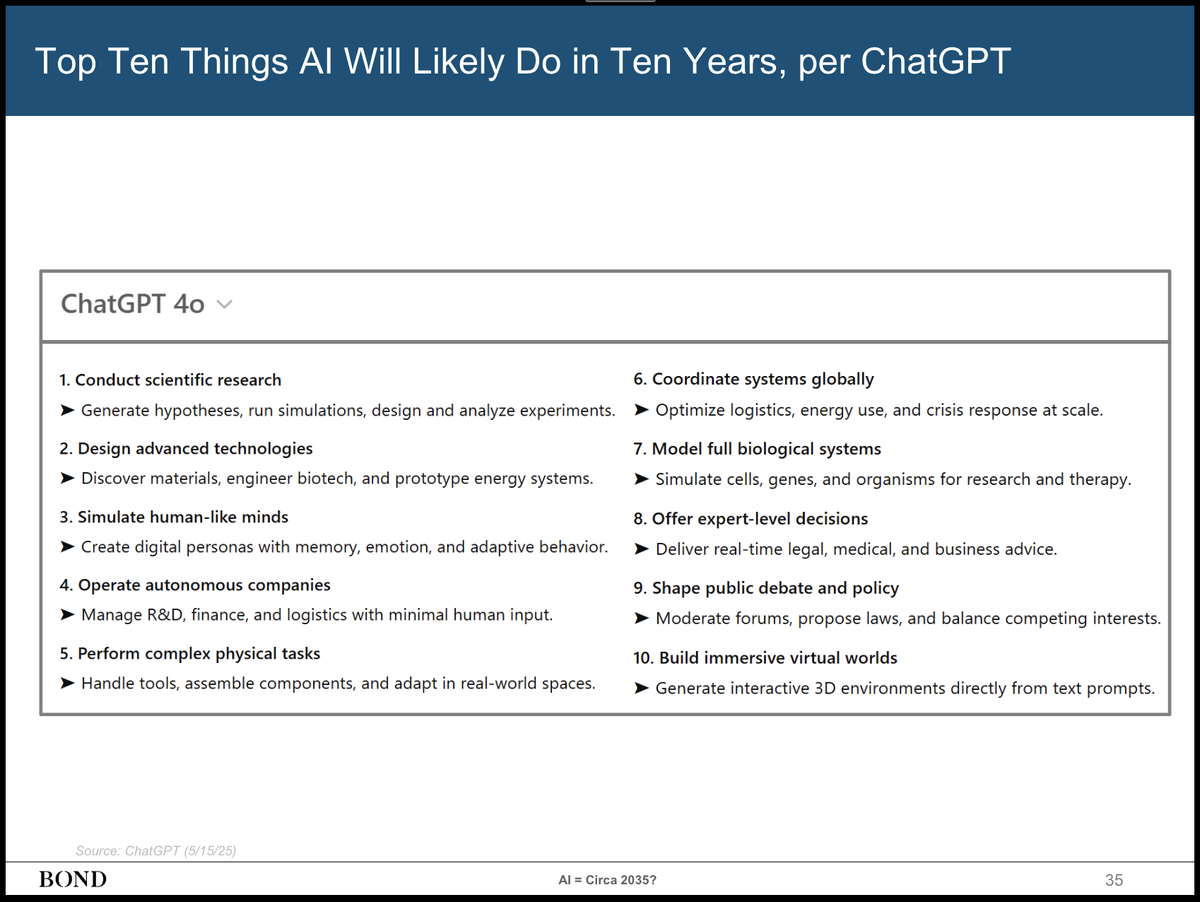

However, Meeker’s presentation presents an accelerated image that I think raises some cause for concern, with a warning: the predictions come from chatgpt (which is an even greater cause for concern).

In 2030, for example, it predicts AI’s ability to create full -length movies and games. I would say that Geminis VEO 3 is proof that we are well on our way.

It promises AI’s ability to operate human-like robots. I would add that the AI time has accelerated humanoid robot development in a way I have never seen in my 25 years of covering robotics.

It says AI will build and run autonomous companies.

In 10 years, Chatgpt AI thinks will be able to simulate human -like minds.

If we remember that Chatgpt, like most LLMs, bases most of its knowledge on the known universe, I think we can assume these predictions are, if something, underambitious. Even ai don’t know what we don’t know.

There were some argument in the office that I was wrong. There is no AI model law, there is just Huang’s law (for Jensen Huang, founder and CEO of Nvidia). This law predicts a doubling of GPU performance at least every two years. Without the power of these processors, AI stalls. Maybe, but I think the power of these models has not yet obtained the treatment force provided by NVIDIA’s GPUs.

Huang simply builds for a future where every person and business wants GPU-based generative power. This means that we need more processors, more data and development jumps to prepare for models to come. However, model development in real time is not hindered by GPU development. These generative updates happen much faster than silicon progress.

If you accept that there is one thing like AI time and that the AI Model Act (heck, let’s call it “Ulanoff’s Law”) is a real thing, it’s easy to accept Chatgpt’s view of our impending reality.

You may not be ready for it, but it will come anyway. I wonder what chatgpt thinks about it.